Priced Out of Decarbonisation

3rd March 2023

Author: Christopher. J. Parker

In 2023, we are all aware of the effect human activities are having on the natural world, and through this understanding, we must actively seek ways of reducing our greenhouse gas emissions.

After two years of painstaking house hunting and failed purchases I and my partner can finally call ourselves homeowners. Thanks to the volatility of the housing market and the infamous mini budget of Liz Truss’ passing premiership, we have been limited to a two bed Victorian terrace, originally built in 1897 for local quarry workers. Other houses were either financial bubbles ready to burst or getting snapped up far to quickly to even have a chance. While far from the dream home it is our home, and a home full of interesting widespread challenges that have my engineer’s brain racing 24/7.

In West Yorkshire, the majority of housing are ex-factory worker housing. To criminally summarise the modern history of the county, the location of the towns with respect to the sheep farmers of the Dales and the abundance of rivers in the South Pennine valleys provided the perfect environment for textile factories, once upon a time churning out the global supply of woollen products. To support this industry, the factory owners built and sold terrace housing for their workforces, providing all the homely needs of the time. Many of these homes remain standing and represent over a quarter of housing in the country (Paddington, et al., 2020).

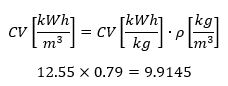

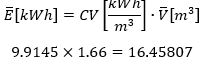

As soon as we received the keys I inspected the boiler, seemed to be the sensible thing at the start of Winter. Flicking through the available documents, it turns out the boiler is over 20 years old and non-condensing! After taking some readings for an hour operation of the central heating system, I calculated it averages 1.66 m3 of natural gas for an hour of heating. For some basic mathematics:

Assumptions

Natural gas consumption per hour: 1.66 m3

The calorific value of natural gas: 12.55 kWh/kg (Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022)

Density of natural gas: 0.79 kg/m3 (Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022)

Cost of natural gas: 10.33 p/kWh (Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, 2022)

Calculation

Calorific value by volume: 9.9145 kWh/m3

Average energy use per hour: 16.45807 kWh

Therefore

Average cost per hour: £1.70

Good grief! That’s 170% of my expectations, even with the high gas prices. Nipping this in the bud I decided to budget for heating upgrade alongside everything else that needs doing to a 125-year-old house to bring it up to modern sustainable living standards.

This leads to financial compromises where possible. For the heating upgrade there are two realistic options. Either a gas boiler replacement with a modern efficient model, or an air source heat pump installation.

The terrace house has a rear yard where a heat pump can be located however, not every property does. After careful thought I’ve chosen the upgrade not only suitable for my situation but nearly everyone living in these types of homes. Boiler replacement.

Unfortunately, it does come down to cost. Even with the UK Governments grant scheme reducing heat pump installation costs to approximately £5,000 (assuming £10,000 installation), it is still more than double the cost of a modern boiler replacement. Balance that with the other works required to keep the property up to current living standards, the extra cash can go to other aspects of the aging property whether that’s electrical upgrades or insulation installation. My partner and I are fortunate enough to have jobs that bring in enough money for us to pay for the property upgrades needed by the end of next year, but the simple truth is the majority of people who live in these properties will struggle to afford the heat pump, and any further investment in the property will be lost as there is a ceiling limit to the property value.

This leads to a social conundrum, a new “class” divide between the rich and poor, or those who can afford decarbonisation* and those who cannot. To tackle this fledgling problem several solutions are possible.

First and foremost is the expansion of subsidies in the technology, lifting the industry off the ground and bringing the wholesale cost of the technology down to a level comparable with boilers. This is the present strategy, unfortunately limited by additional factors. Currently, the manufacturing capacity of domestic heat pumps in the UK is too low to meet the national challenge and unresolved importing issues limit the ability to bring in affordable units. Further expansion of UK manufacturing is essential for this strategy to work.

Secondly, financial packages on purchasing heat pumps like purchasing a sofa can help homeowners balance the affordability of the technology. Paying in budgeted monthly instalments over a period rather than a single up-front fee will make heat pumps more accessible.

Thirdly, forget about installing 28.5 million heat pumps on every home in the country (Paddington, et al., 2020), connect to district heating networks. Star Refrigeration’s Clydebank District Heat Pump facility in Glasgow was an eye-opening project. It debunked several concerns of mine chief among which was the distribution of heat over lengths of pipework without losing too many kelvins. As it turns out the losses are negligible, and the delivery temperature can be guaranteed. A district heating system enables the costs to be managed by local authorities and paid for by either local taxes or metered rates like our other utilities. Any reservations about the need to dig up roads and pavements to lay new pipework are, in my opinion, unwarranted as our other utilities are located underground and the recent fibre optic upgrades across the country demonstrate the modern capabilities of installing further underground utilities.

Communal heat pump systems are already in manufacture and being installed. Clade Engineering have built and installed several systems for residential apartments in the Leeds City area who will pay for the systems through their agreed maintenance fees, spreading the cost and improving the affordability.

There is no technical limitation to heat pumps preventing their adoption in domestic settings. There never have been, it is the substantial upfront cost associated. Until heat pumps become affordable to the average UK household through additional subsidies or communal/district heating schemes, millions will be left priced out of decarbonising their properties.

*Heat pumps for decarbonisation

Heat pumps do not eliminate the environmental impact of heating, but they do reduce it. For example. Take a property that requires 10,000 kWh of space heating per year. This figure does not change whether a heat pump is installed or not.

For a natural gas boiler

Equivalent carbon dioxide on combustion: 200 gCO2e/kWh (Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022)

Assuming a 100% efficient combustion

Annual emissions are: 2,000 kgCO2e

For an air source heat pump:

Seasonal coefficient: 2.5

(I prefer to investigate the annual trend, perhaps in a later article)

Equivalent carbon dioxide of electricity: 193.38 gCO2e/kWh (Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022)

Annual operational emissions: 773.52 kgCO2e

That is a 61% reduction in operational heating related emissions. Limiting the refrigerant charge to natural refrigerants will keep the leakage emissions a negligible factor considering the operational benefit. This is the LED lighting of the heating industry, a low hanging fruit so let us make it accessible sooner rather than later.